Something from Nothing: A Holiday Ramen Masterclass

Turn your turkey (or whatever) into a world-class bowl

Yesterday I received the following email, forwarded on from the great ramen evangelist James Chant, owner of Cardiff’s Matsudai Ramen. It’s some lovely feedback on a collaboration turkey ramen kit we’re selling, with a portion of the revenue going to charity.

Outrageous? Obscene? Heck, what did you do here? Christmas came early.....

It's the soup mum made from the carcass and pickings and it smells like Christmas dinner.

Who'd have thought ramen could bring back childhood Christmas memories to a couple of 'senior citizens'?

But with a 'twist', mum didn't do 'confit'.....

Confit leg? Crisped up 'crispy'. Sous vide breast? Remained super tender.

Pickled cranberries? Cut through the fabulous richness of the soup. Crispy shallots? Aromatic. Reminded me of stuffing, (sort of!)

Guys, it's a masterpiece, it's astounding, obscenely delectably outrageously good.

Massive festive hugs to all of you, from a couple of old duffers

First of all, let’s all take a moment to appreciate the phrase ‘old duffers.’ I don’t know what an old duffer is, but I look forward to being one someday. (Maybe I already am one.)

I’m not posting this to toot my own horn or try and sell more kits – it’s just to share a lovely message that brought a tear to my eye. I’m also sharing it to say that turkey ramen isn’t just a gimmick. It really, really works! And you should make it.

I set some rules for myself when I started this newsletter. One was that this is going to be about American food – not Japanese, not anything else. Another rule was that I would share general guides or work-in-progress reports on how I make certain dishes for free, while actual, detailed, fully tested recipes would be behind a paywall.

Welp, rules are meant to be broken, I guess.

What follows beyond the paywall is a not technically a recipe, but a pretty damn detailed guide to making ramen based on the roasted meat of your choosing – any meat. Thanksgiving has come and gone, so for any Americans reading, it may be too late for turkey, but not for British folks having it for Christmas. And I’ve provided specific tips for pork, ham, beef, lamb, duck, goose, or chicken as well.

This is a methodology, not a recipe – a series of principles, tips and techniques rather than a prescriptive list of measurements and instructions. It will work for anything, and can be fine-tuned. In fact, it should be fine-tuned. Ramen is finicky business, both in terms of how it’s made and how any given slurper thinks it should taste. This will help you make it your own.

Come to think of it, maybe I’m not breaking my own rules. Maybe this is a complete recipe, and maybe it is American. After all, what is a recipe other than a piece of writing that teaches us how to cook something successfully? I reckon this ticks that box. And maybe this is even American, too. Turkeys are American as hell,1 and so is soup made from their bones (with or without noodles).2

Note: if you have my book Ramen Forever, it contains a turkey ramen recipe as well as a lot of tips along similar lines to what I am posting here. So maybe don’t pay to subscribe if you already have that book. You might be disappointed. However, this article does have plenty of new information, including recommendations for specific noodles and where to buy them (in the UK). And besides, all subscription moneys are donated to progressive charities. Last month's takings of £85.99 went to the AAUW of Racine, Wisconsin. So if you want to support me while also supporting some good causes, by all means, get yourself a paid subscription (or gift one to someone else)!

This method is structured around the five elements of ramen: noodles, broth, tare, aromatic fat or oil, and toppings. These are all important to consider individually, but I have always believed that ramen success can only be achieved when you think about how all of these elements interact with each other. Key among these interactions are how the noodles carry and convey broth and toppings, and how the tare seasons everything else in the bowl.

Let’s talk about the noodles first, as this is the hardest thing for home cooks to nail.

ELEMENT ONE: NOODLES

First of all, for the uninitiated: ramen noodles must be ramen noodles. Not udon, not soba, not rice noodles, not somen, not shirataki, not glass noodles, not spaghetti, not chow mein, not yakisoba noodles, not lamian, not anything else. RAMEN. Wheat flour noodles (sorry, coeliacs) made with kansui: sodium carbonate and/or potassium carbonate. E500 and E501, respectively. These compounds are added to ramen noodle dough and they affect its gluten structure in all kinds of interesting ways, giving ramen its characteristic toothsome texture, ranging from snappy and brittle to strong and chewy. No kansui, no ramen. And more to the point, if your noodles don’t use kansui, they just won’t be very good.

An irksome dilemma of making ramen here in the UK is that it is hard to buy and also hard to make good noodles. Kansui is not that easy to get, and making your own noodles is physically difficult and time-consuming. But supermarkets and even most dedicated Japanese or Asian grocers don’t stock very good noodles, either. I recommend that you have a go at making your own noodles at least once, so you can understand the process and start to think about how you might fine-tune your noodles to suit your own tastes and cooking setup. For specific recipes as well as a comprehensive overview of this process, I refer you to Mike ‘Ramen Lord’ Satinover’s Book of Ramen. This is without a doubt the best English-language text on making ramen and includes a detailed explanation of the noodle-making process. And it’s free!

I don’t have much to add to Satinover’s guide, except perhaps to emphasise the importance of resting. In fact, I would recommend prolonged resting (several hours, or overnight) in between the mixing stage and the sheeting stage, again in between, sheeting and cutting, and again – a day or two – before actually cooking the noodles. This is especially true for low-hydration doughs, which are extemely tough and hard to work with unless you give them lots of time to hydrate. But the benefits in high-hydration doughs are clear as well. They will have a more robust texture, cook more evenly, and have a fuller flavour.

Making noodles is hard, but it’s potentially easier than buying them if you don’t have access to a good Asian supermarket, or an online supplier that can deliver to you. But if you do, I would opt for buying noodles rather than making them. These are the specific noodles I recommend:

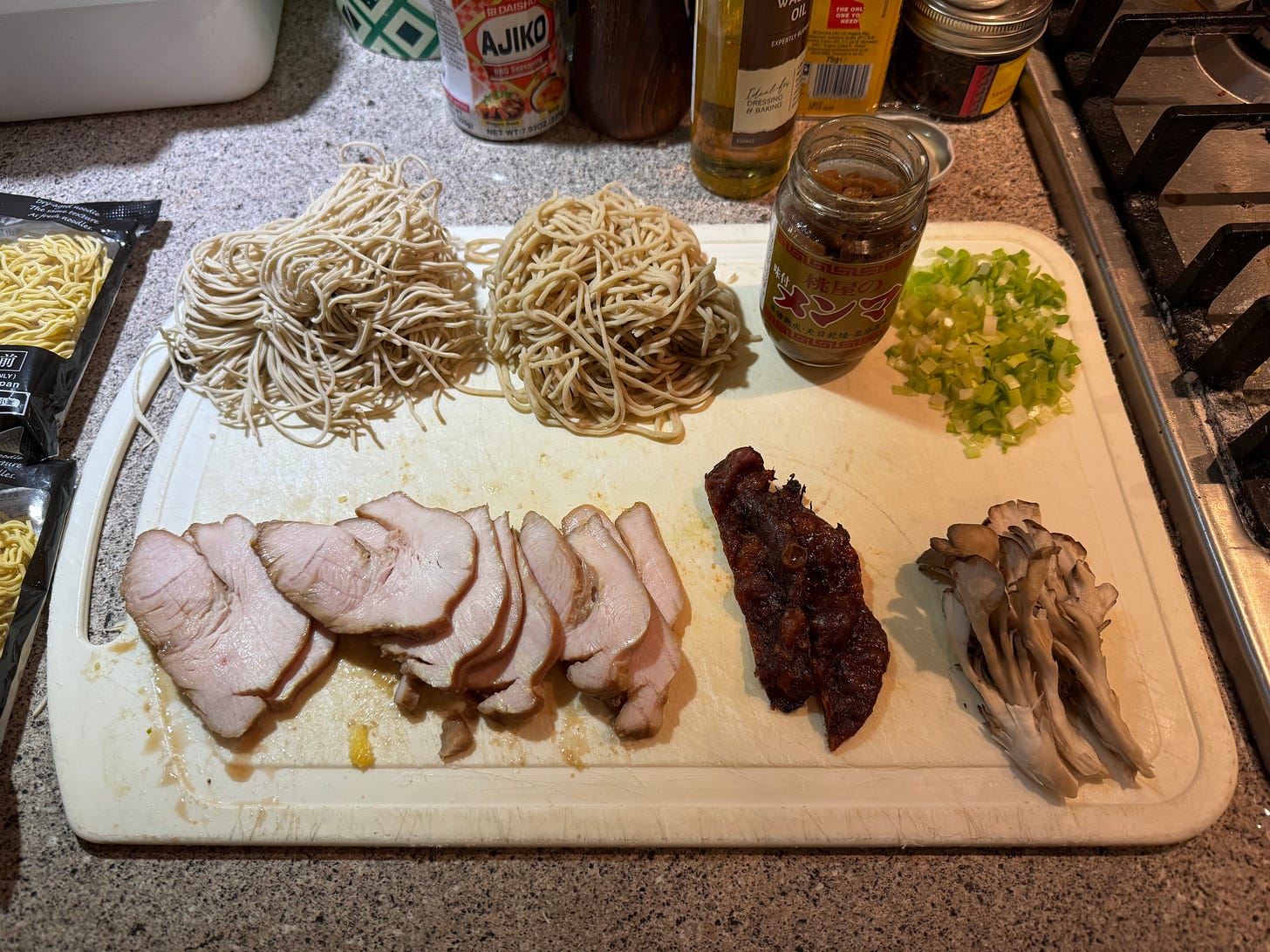

Komugi noodles via Matsudai. These are the UK’s industry-standard fresh ramen noodles, made with love and pride by Omar Rodriguez in Manchester. Matsudai offers three variants for sale on their online shop: thin and snappy Hakata noodles; medium-thick, wavy Tokyo-style noodles; and thick, curly noodles which are based on Sapporo-style noodles but are actually significantly chunkier than what you’d usually find in Sapporo. They are all excellent – worth the £1.99-per-portion price tag. They can also be purchased in a pack of ten. If that sounds like a lot, bear in mind that they can be frozen. But you should take them out of their packaging when you defrost them; as they thaw, moisture can evaporate out of the noodles and then re-condense within the plastic, which can cause the noodles to turn gummy and stick together in places.

Winner ramen noodles or wonton noodles. Winner is a Chinese noodle manufacturer based in London who makes a wide variety of noodles, including very good ramen. Theirs are straight(ish) and medium-thick, making it a versatile option for many different broths, though its texture isn’t as robust or distinctive as those from Komugi. But Winner is hard to beat for availability and cost. Many (most?) East Asian supermarkets stock them, and they can be ordered from several online shops. Oh, and remember how I said that only ramen noodles can be ramen? Well, I lied. Wonton noodles are kind of ramen, too, because they are wheat noodles made with kansui. They are unlike any kind of ramen noodle I’ve had in Japan – long, golden, sulphurous, and very thin but also very chewy, with a slight wave – but nevertheless, they work well in a wide variety of ramen broths, and hold their texture really well.

Dried Nishiyama Seimen noodles from Hokkaido Fine Foods. These are easily the best dried noodles I’ve had in the UK, made by the influential Sapporo-based noodle company Nishiyama Seimen. They are curly and yellow and medium-thick, true to the Sapporo style, and they don’t have the disappointing pasta-like texture that most dried noodles have. There’s just one problem: you can’t buy them anywhere. I got them at the Hokkaido Fine Foods stall at this year’s Japan Matsuri. But send Mayumi-san a message on Instagram – she’s always importing stuff from Hokkaido and you never know when they might get it back in stock.

Samyang or Ottogi plain noodles. These Korean options are essentially instant ramen without the seasoning packets, but they have a great texture as long as you undercook them slightly. They don’t have the resilience of Winner or Komugi’s fresh products, but they are very cheap and convenient. However, their uniform, telephone-cable curl makes them look and taste unmistakably ‘instant.’ They just doesn’t have much personality. Even so, they’re still good, chewy, slurpy noodles that work well in both lighter and richer broths.

Your favourite local ramen shop. If there’s a ramen shop you think serves particularly good noodles, ask them if they’ll sell you a few portions to take home. They might find the request a bit odd, but restaurants always need money, so why not? At my restaurant we’d always sell noodles to whoever asked for them. In fact, sometimes I’d let them have some for free. I was just happy to share the noodle love.

In my experience, most ramen noodles outside of these recommendations are not worth buying. You should especially avoid any cook-from-frozen or similar par-cooked products. Specifically: Yutaka, Sundelic, Sau Tao, and Obento are all common but terrible brands. Don’t buy them. You’re literally better off using spaghetti, or just a packet of Nissin or Sapporo Ichiban.

As you can see, there isn’t much of a range available, and therefore, not much choice. But there are a couple of quite basic but important choices you can make: curly or straight, and thick or thin? Conventional wisdom says that noodle thickness should be dictated by the consistency of the broth. Traditionally, thicker (and higher hydration) noodles are used for for less viscous broths, whereas thinner (and lower hydration) noodles are used for more viscous ones. There is a certain sense to this. Thicker broths are able to coat the noodles easily because they contain more sticky gelatine and fat, whereas thinner broths can be more readily absorbed by noodles because they contain comparatively more available water. Thin noodles rapidly soften through to their core when soaked in lighter broths, whereas thicker noodles have more of a buffer, remaining firm at the centre for longer. Higher hydration also has the effect of activating more gluten, which further helps to delay softening. (Though if you are buying noodles, you are unlikely to know the hydration levels.)

That’s the idea, anyway. In practice, all sorts of noodles work with all sorts of broths, and a lot of this is down to trial and error, and how you cook them. All noodles, thick or thin, will remain firmer in broth if you cook them firmer in the first place. And as for curly vs. straight, this is mostly a question of what you want from the eating experience. Curly noodles are more chaotic. They have more irregularities and are better at entangling toppings, so every mouthful is different. They keep your senses and your brain engaged. Straight noodles are more orderly, more consistent and quicker to chew, and are better at distancing themselves from toppings so they can be enjoyed on their own.

Ultimately, noodle choice is a matter of personal preference. The main thing to remember is to choose ramen noodles (see above), buy good ones (see above), and cook them well.

ELEMENT TWO: BROTH

Here’s something I would never expected myself to say when I was first starting off making ramen: broth is probably the least important and least difficult part of ramen.

This statement is, of course, indefensible. But let me tell you what I mean. You can make a surprisingly good bowl of ramen out of literally just water, provided you have good noodles, flavourful fat, and the right seasonings. Just the other day I made a very tasty little shōyu ramen from chicken powder, two kinds of soy sauce, mirin, Ajiko (which contains salt, pepper, MSG, and ribonucleotides), and goose fat dosed into nothing more than a panful of the Thames’s finest. Would it get me onto any Tabelog rankings? No. But it definitely did the job, more than adequately.

Of course nothing cobbled together like this can have the same depth, character, body, and aroma of a lovingly long-simmered or -boiled broth. It’s just to say that good seasoning, good fat, and good noodles go a hell of a long way towards making a satisfying bowl of ramen. In fact, there is probably no greater shortcut to tasty ramen than by simply combining a generous quantity of chicken fat with good-quality soy sauce. So don’t sweat the broth too much. If you are working with leftovers, you’re limited by what you have anyway, and deficiencies in the broth’s flavour or body can be remedied.

But how to make broth in the first place? This depends on two things: what you’re left with after your roast, and what kind of consistency you’d like. You may not have a lot of control over this, as you’re working with leftovers. You’re not going to be making a rich tonkotsu out of a few bits of leftover pork loin and some rib bones. But don’t worry – you’ll still have tasty ramen regardless. Remember, ramen started off as a dish made from scraps. It doesn’t have to be that fussy. So with that in mind, here’s a little crash course in making broth from whatever you have:

Decide whether clarity in the broth is important to you. If it is, you’ll need to hold the broth at a sub-simmering temperature. Simmering or boiling broths is a more efficient way to extract gelatine, fat, and flavour, but it results in a cloudier broth and somewhat duller flavour, as volatile aromas are boiled off. As a general rule, clear broths (chintan) have less body than cloudy ones (paitan), but they have a more refined aroma.

Gather whatever useful scraps you have. If you have roasted a whole bird, you will have bones and perhaps giblets and little bits of meat. With mammals, your leftovers will vary. Some cuts, like a nice bone-in beef rib, a rack or leg of lamb, or a ham on the bone, will of course yield bones as well. Any large bones should be sawn in half or smashed with a hammer to expose their marrow before boiling. With roasts that aren’t on the bone, you’ll just have bits of meat, fat, and skin to use. Save enough of the meat itself to use as a topping, but use the rest for the broth. The overcooked bits on the ends of a roast and anything tough and sinewy will make good broth. Drippings from the pan – if you haven’t turned them into gravy – should be scraped up and go into the stockpot as well. You can use vegetables, too, but separate them from the meat. You’ll add them later in the cook to preserve their aromas.

Re-roast the scraps (if necessary). Many of the bones and scraps you’ll be working with will have been surrounded by meat and therefore insulated from the strong, dry heat of the oven. This means they won’t have browned much, so put them back in a hot oven for 20 minutes or so to develop more colour. Roasting or browning bones is not common in Japan, but it creates stronger and more complex aromas and more umami compounds. This is an advantage when we don’t have much control over which bones we’re using, or how many. You’ll want to maximise flavour as much as you can.

Put it all in a pot, add water, and boil (or simmer) the bones. Think about yield here: I always aim for 350ml of broth per bowl, plus or minus 50ml. Expect to lose about 20% of the liquid you start with, more so if you add dry dashi ingredients (see step 5 below) to flavour the broth at the end. So if you need 700ml, to make two bowls of ramen (for example), I would start with about 1 litre of water. If you have a lot of bones (a turkey will give you loads), just add enough water to the pot to cover them. You don’t need to be precise at this point.

If you’re making a chintan (clear broth), bring the water to 80-85ºC and hold it there for about 5-6 hours. If you don’t have a thermometer, you can eyeball this. The water should be sub-simmering – you will see some movement in the water as the heat creates currents, and just a few little bubbles breaking the surface every now and then. To maintain this clarity, remove the bones carefully with tongs at the end of the cook, rather than dumping them into a sieve, which will churn up any particles of fat and protein in the broth and cause it to become cloudy.

If clarity is unimportant, you can make a light paitan (cloudy broth). Bring the water to a boil (rolling, but not fierce) and cook, with a lid on the pan, also for about 5-6 hours. You will have to top up the water level periodically during this cook to keep the bones submerged, so don’t pop out to the shop or anything while this is on the hob.Add vegetables and dashi ingredients. Vegetables lose their flavour quite quickly when boiled into broth, especially if they’ve already been cooked. Add them in the last half hour of the cook, unless you are starting with raw veg instead – give these about an hour. Sliced ginger, smashed garlic cloves, leeks, spring onions, cabbage cores, carrots, celery, fennel, and onions are all good additions. The final hour would also be a good time to add a handful of dried mushrooms, if you got ‘em – these need time to fully rehydrate and infuse. But if you happen to have kombu or katsuobushi at home, add these after the broth has been taken off the heat. They infuse better at sub-simmering temperatures, so just let them soak for about an hour before passing the broth through a sieve. In addition to its powerful umami and briny aroma, kombu has the advantage of adding a little bit of viscosity as well. Katsuobushi is probably unnecessary in most broths – it has a very strong and distinctive flavour, and it’s expensive. So I’d only use it if your finished broth has a very weak flavour.

Taste the broth, and correct for deficiencies in its flavour or mouthfeel. You may taste your broth at the end of its cook and think it is not very good. That’s normal – unseasoned broth on its own is pretty bland, so when you taste the broth, always season it, at least a little bit. In fact, there’s a bit of a technique to tasting broth. Don’t just taste it straight from a spoon dipped into it. You’ll likely end up with too much fat on the spoon, which will give you an inaccurate read on the broth’s overall body and flavour, and it will probably scald your mouth, too. Instead, ladle a little bit of broth into a ramekin, add a dash of seasoning – just salt or soy sauce, and perhaps some MSG will do – and swirl it around. This will give you a clearer idea of how the broth actually tastes, while also cooling it down a bit.

If your seasoned broth still tastes a bit hollow – and if you started with a meagre amount of leftovers, it will – it’s time to doctor it. First, go ahead and whack in some stock powder. Dashi powder is great, of course, although if you have katsuo dashi powder, it can become quite dominant even in small quantities. Instead, I’d generally opt for kombu dashi powder or Chinese chicken stock powder, both of which are a little more subtle. When it comes to chicken powder, look for a brand that has a good amount of actual chicken and chicken fat in the ingredients, as well as some combination of both MSG (E621) plus the umami compounds guanylate (E627), inosinate (E631), and/or disodium ribonucleotides (E635). All of these create synergistic umami when used in conjunction with MSG, and stock powders without them are not good value and generally not useful to us. Knorr and Ajinomoto are your best bets.3

It doesn’t have to be chicken or dashi powder, of course – these are just particularly useful because their salt content isn’t as high as most stock cubes and they have amenable flavours. But, used sparingly, any kind of stock cube or powder can work. I get mushroom stock cubes from my local Polish shop which are delicious, and especially good with beef.

If your broth has the right flavour but feels a bit thin, it can be thickened. The simplest and purest way to do this is to use a cornflour or potato starch slurry. Simply dissolve a little starch into cold water, then pour this into the broth and bring to a simmer. Start with a tiny amount – you don’t want to end up with a sauce, and you can always add more. If you’ve made a cloudy broth or clarity doesn’t matter to you, you can thicken it by blending in some cooked potatoes (possibly also leftover from the roast?) or cooked rice. Of course, none of these starch-based thickening agents will give you the same lip-stickiness as gelatine, so if you are after that particular sensory aspect in your broth, you can always add actual gelatine. Depending on the volume of your broth, a leaf or two, pre-softened in cold water and then dissolved into warm (but not boiling) broth will help provide a satisfyingly sticky slurp.Refrigerate and reheat your broth. Broth is best served as fresh as possible, but if you’re not using it right away, cool it to room temperature quickly by pouring it into a large, open container and setting it in a cold part of the kitchen. (NOTE: This is not how you should cool restaurant-sized quantities of broth.) Once it’s at room temp, cover it and get it in the fridge. It will keep for about a week. When you reheat it, be careful not to boil it. This will cause it to reduce and lose aroma rapidly, giving it a flat, stale flavour. Heat it to a high simmer (90ºC or a little hotter) just when you need it, right before dropping the noodles.

Pretty simple! But I should reiterate that finished broth won’t – and shouldn’t – taste complete without proper seasoning. That’s where tare comes in.

ELEMENT THREE: TARE

Tare (a liquid seasoning base) can be very, very complicated – often, more so than the broth itself. But for our purposes of making tasty soup out of leftovers, just think of it as a shorthand for good seasoning. Decent broth (properly doctored, if necessary) should be pretty straightforward to season well, without the need for an overly complex tare. But seasoning is essential, so it’s not to be overlooked.

Job one for tare is to add salt. And sometimes, this is literally all you need, if there’s enough flavour and umami in the broth. But often it will need a bit of oomph, or you may just want a more complex flavour. In that case, here are some other ingredients which can be mixed and matched to create a full, rounded, and interesting flavour in your soup:

MSG. If you want to preserve the pure flavour of your broth while boosting its savouriness, MSG should be the next thing you reach for after you’ve added some salt. Salt helps put flavours in bold; MSG underlines them, which apparently isn’t an option for formatting on Substack?!? Wtf, this ruins my visual aid. But you get the idea. Salt brings flavours into focus; MSG gives them a lasting impact.

Soy sauce. Sometimes, good-quality soy sauce is all you need. It adds salt, umami, richness, and aroma. Use a blend, if you like – usukuchi for salinity, koikuchi for balance, tamari for richness and colour. And if you can get one, I highly recommend an unpasteurised soy sauce – they have such a fresh, full flavour. My favourite is made by Yugeta, but the widely available and much cheaper Kikkoman nama shōyu is quite good too, and it comes in a clever bottle that keeps air out so it doesn’t go stale. Soy sauce goes with everything, but I think it is particularly good with poultry or beef.

Miso. Like soy sauce, miso has a very full flavour that adds salt and umami as well as sweetness, aroma, and a touch of acidity to broths. Also like soy sauce, ramen broth often benefits from using more than one kind (and an unpasteurised variety, if you can get one). It stands up to strong flavours well, so it can be mixed with aromatics like grated garlic and ginger or sesame oil before being cooked out and combined with the broth. Unlike when making ordinary miso soup, in ramen, miso is typically boiled into the broth, and even slightly caramelised or toasted in a wok beforehand. Miso has emulsifying properties, so boiling it into the soup can also help improve the body of broths that may be a bit thin. The funk of miso works well with the funk of gamy meat, so it’s a good choice for pork or lamb.

Fish sauce, yeast extract, mushroom powder, and gravy granules. All of these ingredients will add varying levels of salt, umami, and viscosity to your broth. Of course, some of them are pretty punchy – a dash or two of fish sauce in the broth will make it taste bold and meaty, whereas much more than that, and it’ll just taste… you know, fish saucy. The same goes for Bovril or Marmite – a little goes a long way. Mushroom powder won’t add salt but it will deliver bags of umami and a bit of mouthfeel, whereas gravy granules will (obviously) increase the viscosity of the broth while also bringing our old friends E621 and E635 into the mix.

Curry paste, tahini, and gochujang. Pastes such as these can take your ramen in bold new directions while also adding body. They won’t be the basis of your tare (tahini and some curry pastes won’t have any seasoning in them at all), but think of them as bolt-ons. A few spoonfuls of tahini will take you towards a tantanmen, while a bit of gochujang can be used to transform ordinary miso ramen into a bold spicy miso ramen.

Something sweet. Mirin or a bit of sugar – used judiciously – can bring balance and a moreish quality to the broth. It also works well to temper the heat of chilli, so if you are making a spicy ramen or adding chilli oil, consider a spoonful of sugar. As for mirin, in most cases, cheap ‘mirin-style seasoning’ will do, but there is no doubt that the nutty, sherry-like quality of hon-mirin adds a sophisticated flavour to ramen broth.

Sake or wine. Cooking sake has a lot of umami, as well as a subtle, earthy fragrance and a small amount of acidity and sweetness. It is good for balance and for reigning in the stronger flavours of soy sauce or miso, or to add a little character to a broth seasoned just with salt and MSG. Wine works reasonably well in its place, though it is often much more acidic, so be careful. White is more versatile, but a little red wine (or even port) is great for flavouring beef or lamb broths. Just don’t add so much that the whole soup turns red. That would be weird.

By the way: ramen is often divided into the broad categories of shōyu/miso/shio, but in practice, these seasonings can be blended. Many miso ramen contain shōyu or salt to reduce the overall viscosity of the soup; many shōyu contain a salt solution in order to lessen the impact of the soy sauce and prevent it from becoming too dark or overpowering. Feel free to play around with all three.

In professional ramen shops, tare are kept separate from the broth until serving, so it doesn’t reduce and alter the salinity of the soup, allowing the chef to maintain a consistent level of seasoning from bowl to bowl. At home, however, this doesn’t really matter – you can just add the seasoning directly to the broth, tasting and adjusting as you go. Remember that whatever you use to season your soup, always start with less and add more if you need to. Under-seasoned broth is easy to fix. Over-seasoned, not so much. And on that note: the broth should be pretty damn salty – it will inevitably be diluted by a little bit of cooking water from the noodles, and more so if you add a fat that isn’t seasoned on its own. David Chang used to say that ramen broth should be too salty. I mean, it’s not really true – too salty is too salty – but it’s still something I keep in mind whenever I make ramen. Bring it right up to the edge.

ELEMENT FOUR: AROMATIC FAT

Your broth is done and well-seasoned. Hooray! It’s all coming together. But wait… there’s more!

Adding a flavourful oil or fat to the bowl is an easy way to add even more body and aroma. It’s also an opportunity to shift the overall flavour of the bowl in different directions. Want it to taste more chickeny? Add chicken fat (obvs). Spicy? Add chilli oil. You get the idea. You don’t even necessarily have to make something new here. The rendered fat from your roast, or the fat that settles at the top of your broth when it cools – that stuff is great, and it is likely all you need. But you can also infuse it, if you like, with things like garlic, ginger, shallots, citrus peel, pepper, etc. Or you can add something totally different – and something straight from the cupboard is totally fine. Sesame oil is a classic choice, for example. But I’ve found walnut oil is very nice with turkey, and olive oil (not too much!) is delicious with miso broths.

Shop-bought dripping, lard, or goose or duck fat are great for this, especially if you splurge on some primo stuff – for example, Hawksmoor dripping or Brindisa Iberico lard. Solid fats can be placed directly in the bowl, which you can then set in a low oven (60ºC or so) to warm the bowl and melt the fat. However, if you are after the sparkling visual of fat droplets glistening on the surface of a clear bowl, melt the fat separately and then drizzle it on at the end.

ELEMENT FIVE: TOPPINGS

With good noodles, broth, tare, and fat, you’ve already got yourself a pretty good bowl o’ ramen there. Toppings are the icing on the, uh, soup, as it were. There are some principles to bear in mind when adding toppings. First: less is more. The main attraction in a bowl of ramen is the singularly satisfying experience of hoovering up hot, flavourful soup along a conduit of springy noodles. Anything that gets in the way of this is problematic. Toppings should be integrated with the broth and noodles, not get in the way of them or interrupt them.

Here’s a concrete example of what I mean. I went to get some pho at a place in Catford a while back. I don’t know anything about pho but I enjoyed it. It had a lovely, light but aromatic broth, and the noodles were silky and supple. But the toppings were absolutely texturally at odds with the noodles – so much so that I actually injured myself.

The bowl was covered in raw onions (crunchy) and sliced beef (chewy). So along with the noodles, there were three different things the bowl that required totally different mechanics of biting and chewing. Now, like I said, I am not experienced with pho – it’s very likely that there’s a technique to eating it I don’t understand – but for me these incongruous textures caused me to chew my food in an erratic and awkward way. My mouth can’t multitask. And this resulted in me biting the inside of my cheek so hard it caused blood to drip into my soup.

Again, perhaps ramen-eating technique should’t be applied to pho. But this also speaks to one of the reasons ramen has always been more appealing to me than pho (or indeed, all other noodle soups): it eats in a way that is uniform and consistent, yet still full of contrast from slurp to slurp. A good sandwich or burger is similar: easy to bite through and to chew, and yet each mouthful has varying flavours and textures. A bit of tangy cheese there, some crunchy lettuce here, a juicy tomato there. Such is good ramen.

With this in mind: a good bowl of ramen should have enough toppings to keep things interesting, but no more than that. You shouldn’t have too many textures in a bowl of ramen, and the ones you do have should be compatible with the texture and of the noodles. Perhaps is why so many ramen toppings don’t require much chewing: the jellied texture of a boiled egg, soft-braised chashu, snappy bean sprouts and bamboo shoots, etc. And toppings with a more robust texture, like spring onions, kikurage, or nori, are typically prepared in a way that renders them easier to slurp and to chew.

But which toppings to choose? Well, there are a few which are standard and work on most bowls. The first is chāshū, of course – traditionally pork, but in this case, you’ll be using whatever leftover roast meat you have. In general, roasting is a cooking method that doesn’t yield the most tender results, so this should be very thinly sliced so it isn’t too chewy. You may also want to marinate the meat in some soy sauce, something sweet (like sugar, mirin, or honey), something rich (like oyster sauce or tamari) and perhaps some aromatics like crushed garlic, ginger, or pepper.

The second most common ramen topping is spring onions. These are pretty straightforward, of course, but in some bowls their flavour can be a bit too sharp. Soaking sliced spring onions in cold water for about half an hour will help to remove some of this harshness, and it also helps to rinse out any grit inside of them. (Don’t bother washing spring onions before slicing them – you won’t be able to get at the dirt stuck way down within their stalks.) A nice alternative to spring onions is finely-diced leeks, which glimmer like shards of stained glass atop a fat-dappled chintan.

Chāshū and spring onions toppings are basically prerequisite, but beyond that, think about what the bowl needs. A lot of ramen benefits from something pickly: beni shōga (NOT gari) is a good, versatile choice. Menma is another – just make sure you use actual Japanese marinated bamboo shoots and not just ordinary ones out of a tin. The texture and flavour is all wrong. In ramen that wants a bit of spice, you can use karashi takana-zuke (spicy pickled mustard greens) or kimchi, but be careful with these, as they can easily overpower the bowl, and kimchi’s strong sourness in particular is pretty unorthodox in ramen.

If you want to add some sweetness and a rich, enticing aroma, fried alliums are a nice choice. My favourites are thinly sliced shallots which have been slowly fried in oil until evenly browned and crisp. Their texture goes from crispy at first, to slightly chewy and jammy as they begin to soak up broth, and finally, silky and ethereal as they fully soften. Fried garlic is also delicious, and don’t be afraid to take it quite dark – the bitterness will work well with richer broths, especially ones made from pork (as seen in the popular addition of burnt garlic oil to tonkotsu).

Dry seasonings can also add some interesting layers of flavour to your bowl. Toasted sesame seeds are pleasant and nutty and add a little texture, too. (Don’t use black sesame. They look weird, like mouse poo.) For spice, gochugaru, Aleppo pepper, black or white pepper, sansho, yuzu-koshō, and shichimi work well. And if you have katsuobushi on hand, you can whizz it up in a spice grinder to make gyofun: fish powder. A pinch of this in the base of a bowl will add a smoky aroma, slightly fishy funk, extra umami, and an interesting fine-grained mouthfeel. I like it in particular with chicken or lamb.

Finally, consider some vegetables (for your health!). Blanched bean sprouts or chopped hispi cabbage are mild enough to work well in most bowls, and integrate well with noodles. Kikurage or sliced rehydrated shiitake mushrooms add an interesting fungal texture (though kikurage are basically flavourless). Tantanmen is often garnished with bok choy, although to be honest this has always kind of bothered me because it is hard to bite. I prefer chopped Chinese leaf or morning glory if you want something similarly green and crunchy, because they are easier to eat and soak up broth better. In other words, they slurp well.

Spinach is also nice, though only if it’s proper large-leaf spinach so it actually has some texture. Blanch it and shock it in ice water, then gently wring it out and cut it into neat bundles before adding to the bowl. Along similar lines, you can add wakame, which has a spinachy flavour and texture, but is easier to prep – simply rehydrate it and you’re good to go. And of course, there’s always our old friend nori – rest it on the side of the bowl, and either eat it right away so it’s still crisp, or let it soak in the broth for a while to soften completely. Anything in between is like chewing on a wet tissue. Lastly, spicy ramen – like tartanmen, curry ramen, or spicy miso – is nice with some coriander on top (but it is completely out of place in other styles).

That just about covers it, but remember: less is more. Think about what you want in terms of flavour and texture before you start chucking things on top with reckless abandon. It may be that you don’t really need much more than the classic trio of menma, nori, and chashu. Most ramen doesn't!

Sorry, one last thing: EGGS! This warrants a whole other post, so for now I’ll just direct you to Preston Landers’s detailed and highly regarded ajitama method. I don’t have much to add to this other than that when it comes to both cooking and peeling eggs, it will require lots of trial and error in terms of both timing, starting temperature, and the brand of eggs you buy. Some peel better than others, and of course some taste better than others. But I will also add that older eggs are easier to peel, because as they age, the white inside loses mass through evaporation, causing it to shrink and pull away from the inner wall of the shell. So if you know you’re going to be making ajitama, hold onto some eggs until they’re approaching their best-by date.

GAME PLANS BY MEAT

Making ramen is about iteration. To make decent ramen you have to constantly evaluate your bowls and make adjustments as needed. What does it need? What doesn’t it need? I cannot answer these questions for you. But I will also say that sometimes these adjustments can be made on the fly, even at the table. While some ramen shops in Japan are very particular about their product and don’t allow much in terms of customisation, others offer a little library of tabletop condiments to re-season the bowl however each customer likes. Soy sauce, pepper, chilli oil, extra tare, vinegar (sometimes infused vinegar), raw garlic, crushed sesame – go for it. There is no point in being precious about your ramen if you (or anyone else) thinks it needs something. There is also the whole concept of ajihen, or ‘flavour change,’ which is when you add something halfway through the bowl to alter it or completely transform it, keeping it interesting until the very last slurp. Yuzu-kosho and sansho are a couple of my favourite go-to ajihen.

With all of these general principles in mind, you should be well equipped to make pretty good ramen out of your leftovers, whatever they are. But if you are in need of more specific inspiration, here are a few ideas on how to treat various kinds of meat:

Pork: Take inspiration from the light pork broths of Asahikawa shōyu or Hakodate shio ramen. The former uses a ‘double soup’ of pork broth blended with fish dashi, seasoned with soy sauce, and covered in plenty of hot lard. The latter can use a straight pork broth, seasoned with salt and MSG, but I’d also infuse plenty of kombu into the soup, or add a generous sprinkle of kombu dashi powder. Hakodate shio can also be dosed with a spoonful of lard, but it can also use chicken fat (or in this case, duck or goose fat, if it’s going). Both styles can be served with medium-thick, straight or slightly curly noodles, and topped with thinly sliced pork, spring onions, menma, and nori. Both styles are also delicious with freshly grated ginger, either added directly to the bowl or provided as an ajihen midway through the meal.

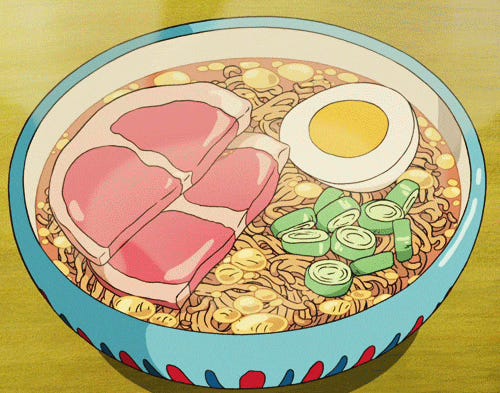

Gammon: Recreate the iconic shōyu ramen topped with ham from Ponyo. This appears to be a curly-ish (instant?) noodles in a light, clear broth, perhaps seasoned with some salt in addition to soy sauce so it is not too dark, and simply topped with ham, half a boiled egg, some chunky chopped spring onions, and plenty of golden fat. It looks like chicken fat but sesame oil mixed with any animal fat would be delicious.

Image via Food is a Four Letter Word. Beef: Though it may sound gimmicky, French onion ramen is exquisite and quite easy to make. Fry some very thinly-sliced onions in dripping or olive oil until nice and dark (no need to properly caramelise them), then add a glug of red wine or port. Top this up with your beef broth (ideally infused with dried mushrooms and/or kombu) and season with soy sauce, mirin, and maybe some Bovril or a beef stock cube. Serve with chunky noodles such as Komugi’s Sapporo-style, a drizzle of sesame oil, menma, black pepper, blanched spinach, and thinly-sliced rare beef. Garlic bread on the side would be an exceptional idea as well.

Lamb: Lamb loves curry, and lamb loves miso. Therefore: lamb curry miso ramen. Combine whatever miso you like with whatever curry paste you like (I really like this one) in a hot wok with some oil (neutral oil is probably best) and let it brown a bit before chucking in a handful of sliced onions, cabbage, and bean sprouts. Stir-fry for just a minute to get a bit of char on the veg, then add your leftover lamb broth and bring to the boil. Tip the soup and veg onto Sapporo-style noodles and top with sliced roast lamb (or ‘pulled’ braised lamb), crushed white sesame seeds, chilli flakes, chilli oil, spring onions, and coriander.

Turkey: I would go full-on festive with this. Turkey gives a great carcass, which you can boil the shit out of for 8-10 hours to make a nice, rich paitan. In the last hour, infuse this with some ‘Western’ flavours like celery, shallots, sage, bay leaf, rosemary, and garlic. Season simply with salt, white pepper, MSG, and perhaps some sake or white wine for a touch of balancing acidity. This will work with any kind of noodle and can be topped with with garlic-infused oil or duck fat, fried shallots, spring onions, something pickled (I use pickled cranberries but menma or beni shōga will do), perhaps some spinach, and the sliced turkey, of course. (However you normally cook it will be just fine, but for me it is really hard to beat confit dark meat and sous vide white meat. The confit will also yield a delicious fat to add to your ramen.)

Chicken: For me there are few pleasures greater than the pure, simple, old-school combination of chicken, soy sauce, and katsuobushi. Use these as the basis for a classic shoyu ramen, and be sure to set aside plenty of chicken fat to add to the bowl. Use medium-thick ‘Tokyo’ style wavy noodles, and garnish with diced or shredded leeks, menma, and the chicken itself. If you want to make it look really iconic, add a pice of sliced narutomaki and a piece of nori.

Duck or goose: For this I would indulge in a little bit of stupid ‘Asian fusion’ and make a crispy duck ramen. Infuse the duck broth with star anise, cloves, fennel seed, leeks, ginger, and garlic, and perhaps some orange peel. Season with soy sauce and a touch of demerara sugar, and serve with Winner’s ramen or wonton noodles. Crisp the leftover duck in a frying pan with a little sesame oil and duck fat and add both the oil and the meat to the bowl, and garnish with shredded leeks, julienned cucumber, sesame seeds, and maybe some menma. Serve with a little pot of hoisin on the side, to stir through the broth as an ajihen when the soup starts to get boring.

That’s it for today. Thank you for reading. I hope it is helpful! I will be opening up my subscriber chat about this, if anyone wants to ask any questions or share any success stories (or failure stories)! Enjoy your holidays, and enjoy your ramen.

Benjamin Franklin wanted it to be our national bird, instead of the eagle. I agree!

Ramen is Japanese, of course, but then again, what could be more American than taking someone else’s stuff and calling it yours?